Not quite the Bali it used to be? This is what overtourism is doing to the island

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Not quite the Bali it used to be? This is what overtourism is doing to the island

As travellers flock to the island possibly in record numbers this year, the programme Insight explores what lies behind the locals’ love-hate relationship with tourism and what can be done to stem the feelings of discontent.

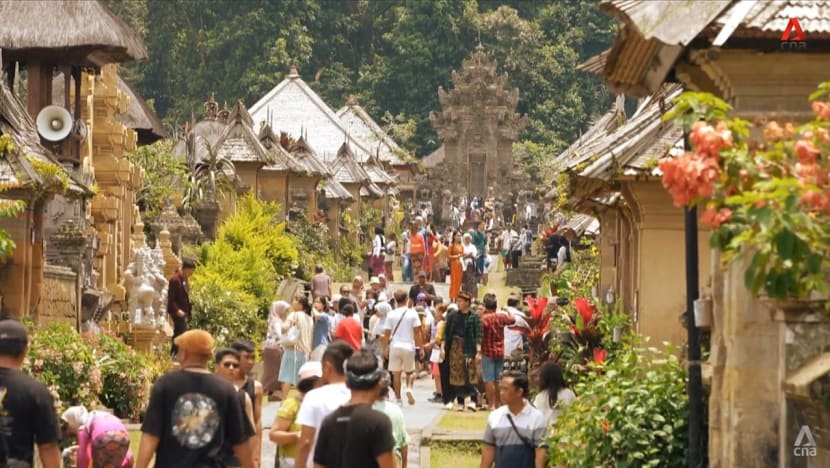

The traditional village of Penglipuran in the east of Bali now attracts thousands of people a day.

But its free and easy atmosphere may not be quite what it was. In February, the local government launched a new tourism police unit to deal with problematic foreign and domestic tourists.

It has handled drunk tourists and even those who beg for money.

“They must’ve been running out of resources and then turned to begging. There are cases like that,” said Dewa Nyoman Rai Dharmadi, the head of Bali’s Civil Service Police Unit.

“Sometimes there are locals who disturb tourists at places of interest. Basically, we remind everybody to create a conducive atmosphere for all tourists.”

More than 70 tourism police officers have been deployed in popular districts, such as Canggu, Seminyak and Kuta.

Part of their job is also to ensure that tourists dress appropriately — for example, by wearing sashes provided — in the temples of Bali, the only Hindu enclave in Indonesia.

“Because of their ignorance, they don’t follow the rules when entering sacred places,” said Dharmadi.

In this slice of paradise, discontent is brewing. Last May, Bali’s then governor, Wayan Koster, proposed a cap on visitor numbers, citing misbehaving tourists as the reason.

Although the proposal did not materialise, the island continues to grapple with its status as Indonesia’s most popular tourist destination.

Last year, Bali deported 340 foreigners, up from 188 in 2022, mainly from Russia, the United States, the United Kingdom and Nigeria. Their violations included overstaying, working illegally and exposing themselves in sacred places.

In December, after a video of a payment dispute in a beauty salon went viral, two female tourists — an American and a Bermudian — were arrested for allegedly attacking salon staff, then deported in February, according to local police.

Earlier this year, police arrested three Mexicans for an alleged robbery that left a Turkish tourist wounded.

As travellers flock back to Bali after the pandemic, possibly in record numbers this year, the problem of overtourism has become more apparent than ever.

Still, Bali wants to have more visitors to make up for lost time, and lost tourism receipts, when the pandemic laid waste to its economy. In 2021, only 51 foreign tourists visited the island, compared with 6.3 million in 2019.

Last year, that number was close to 5.3 million, exceeding the target of 4.5 million. This year, Indonesia’s Tourism and Creative Economy Minister, Sandiaga Uno, has raised the benchmark to seven million, cited Bali tourism chief Tjok Bagus Pemayun.

“That’s quite high,” Tjok told the programme Insight. “Hopefully, we can reach the target because many airlines have added flights to Bali.”

CONCRETE CANGGU

The influx of tourists is not just giving rise to occurrences of misbehaviour, however. It is putting a strain on resources and tarnishing Bali’s image because of rampant development, overcrowding and gridlock.

WATCH: Bali’s love-hate relationship with tourism on Indonesian island paradise (46:24)

Bali made headlines in December when a traffic jam on a toll road forced people to walk up to four kilometres to the airport. There are also constant jams on roads leading to places of interest.

With a population of 4.5 million, how many tourists can the island accommodate, questioned Nyoman Sukma Arida, a vice dean of the tourism faculty at Bali’s Udayana University.

“Do we have enough land and water supply? Tourists need food and so on,” he said.

The latest neighbourhood caught in a developmental dilemma is Canggu, after decades of tourist development spreading north from Kuta beach to Legian, then Seminyak.

There are now concrete buildings on every street in Canggu. Developers are attracted by its relatively cheap land prices. But the area is “suffering from massive traffic jams”, said Sukma, because “there’s no master plan”.

Locals such as traditional community chief Made Kamajaya, who was born and raised in Canggu, have a love-hate relationship with tourism.

“The local people’s economy is getting better,” he said. “(But) our surroundings have changed. You’re seeing destruction behind your house, in front of your house. … We’re dealing with uncontrolled development, of which almost 90 per cent disregards the environment.

“There’s no desire to plant trees. Waste management is non-existent.”

He is worried that “all the unregulated infrastructure projects will threaten tourism itself”.

WORLD HERITAGE SITE AT RISK

Even the rice terraces of Jatiluwih in central Bali — a Unesco World Heritage Site and one of the reasons tourists visit the island — are at risk of urban encroachment.

“There are always new developments,” said tour guide Wayan Kaung. “The process is slow. Usually, it starts with a small hut selling coconuts, and slowly it turns into a restaurant.”

He brings tourists to Jatiluwih at least four times a week. Foreigners pay 50,000 rupiah (S$4.20) as an entrance fee, while Indonesians pay 15,000 rupiah.

“This is valid because I’ve seen rice field destruction near my home. There are many housing complexes, and the regulation of land conversion is unclear. So we must pay to protect something like this,” he said.

But it does not protect the rice fields completely. A 2018 report from the Amsterdam-based non-profit Transnational Institute estimated that Bali was losing 1,000 hectares (1,400 football fields) of agricultural land to development every year in the preceding 15 years.

According to a recent study by Udayana University agriculture professor Wayan Windia, the island is experiencing a deficit of 100,000 tonnes of rice per year.

As much as 65 per cent of Bali’s groundwater goes to the tourism industry, drying up more than half of the island’s rivers and threatening sites such as Jatiluwih.

For some farmers, it is more lucrative to sell their land to developers than to eke a living in agriculture.

“So long as there’s a good view, there’ll be an opportunity to build villas,” said Kaung. “If one person sells his land for villa construction, others will jump on the bandwagon because of the access road.”

Some of the remaining farmers supplement their incomes by making handicrafts.

“Because of the opportunities offered by tourism, villagers work hard to make handicrafts. But they get only a small amount of money. It isn’t fair. That’s what we want to address,” said Agung Alit, the founder of Mitra Bali.

His social enterprise buys and sells handicrafts from these Balinese artisans.

“We invite the craftsmen to work together. We give a 50 per cent down payment, then when the goods arrive here, we check them, we select and pay cash,” he said.

The irony of the situation — that Bali is so dependent on the tourism said to be destroying the island — is not lost on him. “Tourism is ingrained in Bali,” he noted. “And it’ll be a challenge changing it.”

INDIGENOUS AND CULTURAL CONCERNS

Elsewhere, towards the north of Bali, Lake Tamblingan is becoming increasingly popular with tourists. It was formed from an ancient caldera, surrounded by a rainforest called Alas Mertajati.

The lake and the forest help to protect water resources for the indigenous communities, who are mostly farmers. They grow coffee, oranges and vegetables.

The forest has a nature tourism zone, which allows investors, and a designated protected zone. “We’ve seen illegal logging, which affected the forest,” said indigenous leader Putu Ardana. “We don’t want that.”

He is working with the locals to protect the forest. They are lobbying the government to return stewardship of the forest to the villagers. To do so, the government must first recognise the indigenous tribes’ ancestral rights to the land.

Putu has some “harsh” criticism, however, of the government and of investors. “The government treats Bali like lucrative merchandise. Investors offer funds, and the government offers regulations, permits and so on,” he said.

“It shouldn’t be the concept of selling (but of) preserving.”

Culturally, tourism money and interest over the years meant more funds for the upkeep of temples and to hold traditional ceremonies. But some people question whether the pageantry loses its authenticity when put on for a show.

Rucina Ballinger, co-author of the book Balinese Dance, Drama and Music, calls it “cultural degradation” when there is “very little understanding” on tourists’ part.

“(On) the Balinese side, it’s when … they tell (visitors) to go and see these tourist performances, as opposed to ‘go to a warung — a little food stall — sit down, talk to the locals, have a cup of coffee and learn about their life,’” she said.

“Tourists are coming, and they’re … taking pictures. It’s an Instagram culture, it’s ‘let’s go to the beautiful spot’. And now all of these places are making Instagram spots for the tourists. And some people come here just to do that.”

For tourism consultant Lenny Pande, art, culture, tradition and the environment are the four pillars of tourism and are important “because those pillars exist in Hinduism in Bali”.

But she, too, has observed that “the preservation of those pillars is slightly diminishing” because of overdevelopment.

ENVISAGING A BETTER FUTURE

As concern over the impact of overtourism grows, the government has promised a more sustainable future for Bali.

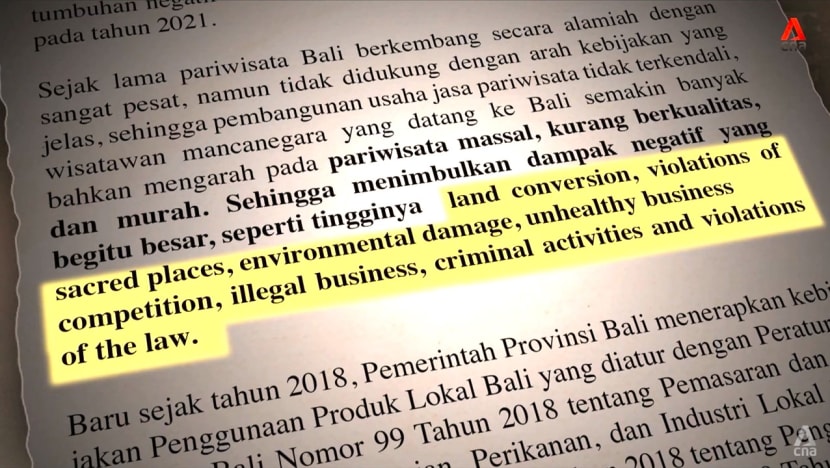

Last July, outgoing governor Koster issued new guidelines on Bali’s development for the next 100 years (2025 to 2125), which cover the protection of nature, culture and the Balinese people.

For the first time, the government acknowledged the impact of mass tourism on Bali, citing land conversion, violations of sacred places, environmental damage and illegal businesses and activities as examples.

“One of the concerns is that Bali is being sold as a cheap tourist destination. Hopefully, we can minimise that so we can do better for Bali in future,” said Tjok from the local tourism authority.

“We want to have tourists who … respect Balinese culture. Secondly, we want tourists who are willing to stay longer. Hopefully, they’ll also spend more money.”

Since Feb 14, the government has levied a tourist tax of 150,000 rupiah. The revenue collected is meant to preserve Bali’s cultural heritage and protect its environment.

“The environment is our big house. The guidance from the top is to use the levy to deal with the waste problem,” said Tjok.

As for traffic management, the measures being taken include the construction of new underpasses. There are also plans for a Light Rail Transit system.

The forces of tourism may prove too strong, however, for some government plans.

In January, a proposed entertainment tax of up to 75 per cent met with fierce resistance in the tourism industry. The steep tax has since been put on hold.

Last May, Koster announced a ban on tourist activities on all 22 of Bali’s sacred mountains, blaming tourist misbehaviour. But activities continued, and the ban is as good as axed.

With the lure of tourist dollars hard to resist for many, it could be up to local communities to preserve their way of life.

In the village of Penglipuran, in the east of Bali, a customary law forbids villagers to sell their land to outsiders. The traditional village is popular among Indonesian tourists, who pay an entry fee of 25,000 rupiah per person.

Tourists are allowed to enter family compounds to look around and buy snacks and souvenirs, so it can be intrusive.

But the money collected from visitors — up to 5,000 a day — has proven useful in protecting the culture and livelihood of the 1,100-plus villagers. During the pandemic, around 3 billion rupiah was distributed among them.

Deputy village chief Nyoman Setiawan is grateful that their culture is “still being upheld”. He said: “So long as our customs are strong, we’re convinced what happens to places like Denpasar, Kuta and Canggu won’t happen to us.”

Indonesia’s tourism ministry says the future of Bali lies in such small-scale, sustainable initiatives.

There is still a need, however, for authorities to first calculate “the carrying capacity of each zone and Bali as an island”, stressed Sukma the academic.

“Next, they must empower the local communities to be involved in controlling what happens in their areas,” he said. “The problem is the communities are … involved only when problems arise.”

As the post-pandemic revival of tourism continues at full steam for now, with every gridlocked motorway, every piece of rubbish thrown in the sea and every paddy field that disappears, a bit more of paradise is lost for some.

“Bali is doomed,” said Ballinger, who is married to a Balinese and has two sons and three grandchildren. “There’s no way that these concrete jungles can be turned back into rice fields … or into something that’s Balinese.”

With the growing attention on overtourism, however, some others see a chance for change.

“If we respect and preserve our culture, other people will be respectful,” said Sukma. “Perhaps it’s the Balinese who are complacent. This is my reflection.”